Let it be said, solfeggio is not indispensable to learn didgeridoo. However, understanding the basics of this language will help you communicate with other musicians, other didgeridoo players and even write your rhythms. In this series of articles, I propose to present the basics of solfeggio.

The purpose of these articles is to help you understand and integrate them in order to train you in musical language. Let us begin by defining technical terms that will serve us throughout this series of articles.

What is a rhythm?

A tour on Wikipedia tells us this: “Rhythm is the characteristic of a periodic phenomenon induced by the perception of a structure in its repetition.

Does it mean anything to you? I’m not! Damn, I admit, that’s not clear.

Let us try to simplify this definition. Let’s say, without being afraid to simplify, that a rhythm is a phrase that we will repeat at constant speed. Remember when you were a kid, you knew how to do it very well! Who has not repeated this kind of song: “I know a song… that annoys people, I know a song…”. Doesn’t that mean anything to you?

I guess you don’t have a problem repeating that sentence over and over again, do you? Well, didgeridoo is the same thing, no more and no less. Only the language changes, but the principle remains the same. So if we start speaking didgeridoo in a simple and understandable language it will give for example :

We have our first rhythm! He will be our example throughout the article. The recording’s coming down!

The tempo

What is Wikipedia telling us this time?

“In music, tempo (from Italian tempo: “time”) is the allure of a musical work’s performance.”

This time the definition is rather simple to understand. In short, tempo is the speed at which a song is played. The higher this one is, the faster the piece will be, and vice versa. The unit of measure for tempo is expressed in beats per minute (Bpm). So, if the song is played at 60 Bpm, we can beat the time 60 times in one minute so every second. Glory to the clock in your kitchen or living room (that works too)! Because its second hand marks a tempo of 60 Bpm. You could say it’s a single-speed metronome.

Therefore, a 120 Bpm song will simply double that tempo. It is generally accepted that an average speed of a song is around 80 and 120 Bpm. Beyond that, it will become fast pieces and below slow pieces. Tempo is essential, because it is the reference point of your song. It allows you to play with other musicians… hence the need to work on the metronome!

A poetic approach also makes us realize that each human being (and animal) has its own inner tempo: the pulsation of the heart. To meditate…

Mediation complete? So back to our example played at two different tempos: 60BPM and 120BPM.

2-stroke rhythm at 60 BPM

2-stroke rhythm at 120 BPM

Pulsation and beat

The pulsation

Wikipedia tells us: “The term pulsation means, in the field of musical rhythm, the accent intervening cyclically at the beginning of each beat. The regularity of the pulsation thus guarantees equality of time, and consequently, a certain tempo.”

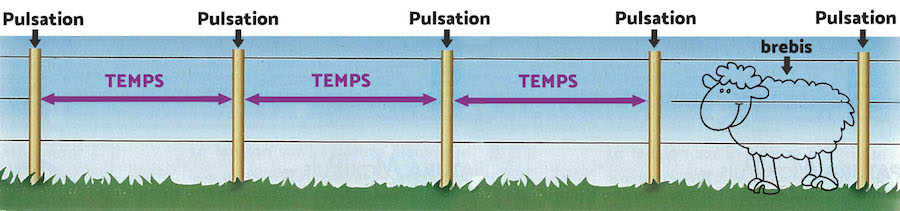

The pulsation is therefore the “beep” of the metronome. Its speed is called “tempo”. The pulsation is therefore a regular sound that determines the duration of time.

The beat

Beat is therefore a duration. It’s a space between two pulses. To use the example of the second hand at 60Bpm, it therefore defines times that have a duration of one second. Do you understand?

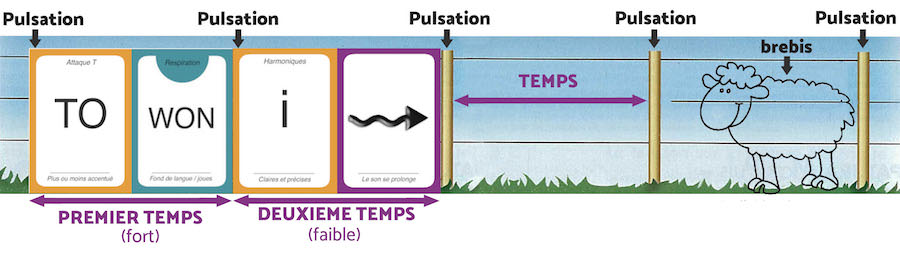

To fully understand this notion of pulsation and time, keep in mind the image of a fence. The stakes represent the pulsation and grid between the stakes over time, quite simply. There are fences with very distant poles and therefore long fences (slow rhythms) and very close poles with a very short fence (fast rhythm). Here is a drawing which should help you to definitively integrate the thing:

Forgive me, I couldn’t help it.

But let’s get back to our business (I’m getting a little heavy here, don’t I?).

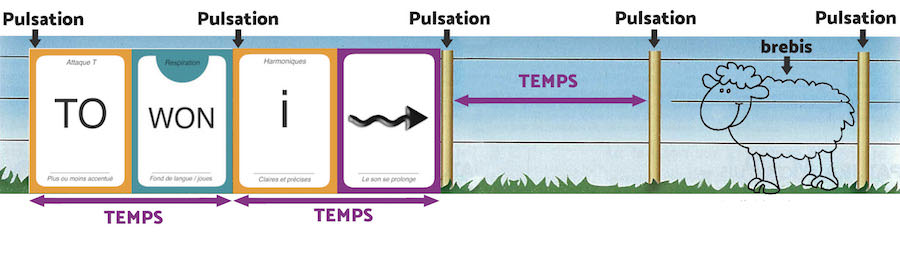

If I superimpose my rhythm cards on my fence it gives:

Do you agree with that? Well with that in mind, you will see that the notion of measurement will be very easy to understand!

What is a measure?

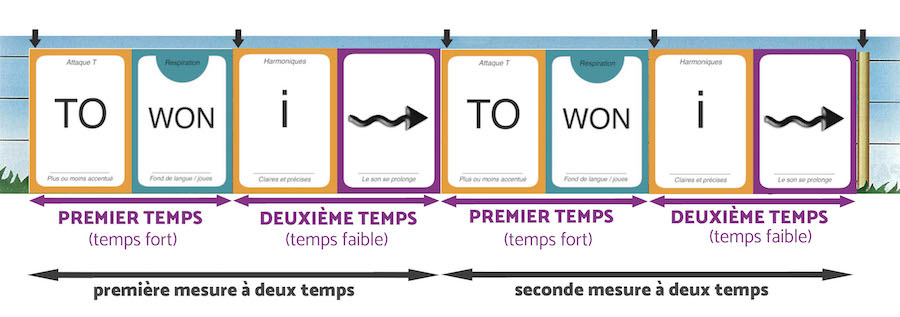

You’ve certainly heard of 2-count, 4-count, 7-count, right? Well this simply tells us that in a 2 beat bar, the rhythm will be composed of a strong beat (the first beat) then a weak beat. Thus, in our example, it is a two beat measurement (or two beat rhythm):

By playing the rhythm twice as below, we will write two bars in two beats:

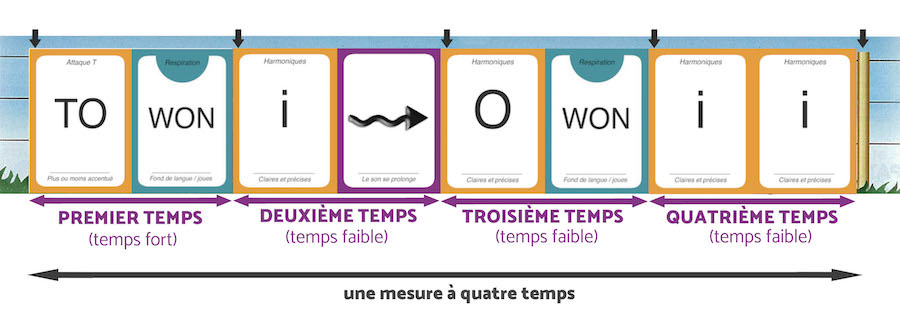

Now that you have understood this principle, we will add two beats to our example to form a 4 beat rhythm. This will give us a strong time (first beat) and three weak beats.

And by adding another beat, with the vowel A for example, we arrive at a rhythm at 5 beats :

And by adding another beat, with the vowel A for example, we arrive at a 5-beat rhythm:

For each recording, listen carefully to the metronome. Count the number of “beeps” before the beat returns to the beginning. In the two beat rhythm, we will have two beats. In the 4 beat rhythm, 4. And in all logic in the 5 beat rhythm, 5. Do you understand the principle? It’s no more complicated than that! We often think that a 7 beat rhythm is complicated to play, they are false ideas. And be careful with that, because everything you think is hard to do becomes hard by definition. For the 7 beats, it is only a habit to acquire. Indeed in our western society, 4 beat rhythms are very widespread so most of us play them very naturally. While 7 beat rhythms are much rarer. And what is less listened to is by repercussions less played. Having said that, start by playing 4-count rhythms and try to dissect them to see where the 4-count falls. Make sure you drop it right on time (see the article on the metronome). Thereafter, it will always be “time” (it can’t be invented!) to make your measurement more complex.

Conclusion: Solfeggio is a musical writing convention

The image we have of solfeggio is that of the complex and unreadable scores of a musician friend or of childhood memories. However, if you get into the game, you will find that the basics are far from as complex as our memories would have us believe. If we overcome our prejudices, music theory is accessible to everyone and has many advantages. It allows to communicate between musicians, but especially to write its rhythms. Then it becomes a great way to share!

I hope you enjoyed this article, feel free to share it and ask questions if you have any! I’ll prepare the rest for you.