You probably already know that the didgeridoo has only one note. Indeed, unlike “classical” instruments such as the piano, violin, or guitar that use multiple notes, all the work of a didgeridoo player consists of breaking down the single note available to extract the maximum sound possible from it. That’s why today, I’d like to take a closer look at the physical composition of this note. And this involves studying the frequencies that compose it. In physics, this is called the spectrum of a sound. Beyond the pure theory we’re going to cover, you’ll be surprised to hear how this can help you develop your listening skills and your playing.

So, are you ready to get frequencies in your ears (and eyes)?

Let’s dive into didgeridoo physics!

Each note corresponds to a frequency

It’s important to understand that each note vibrates at a “main” frequency. This is called the fundamental and it determines the name of the note. For the didgeridoo, the fundamental is therefore the note of the instrument. This is why we talk about a didgeridoo in C, in D, in E… etc.

That said, you have every right to say: “Okay, but what’s this story about frequencies?! I mean, concretely, how does it work?!”

Good point, dear reader, your insight delights me! Well, we can define frequency as follows:

Frequency is the number of vibrations (of air) per second. Frequencies are expressed in Hertz (Hz). This name finds its origins in the name of Mr. Hertz who discovered these frequencies.

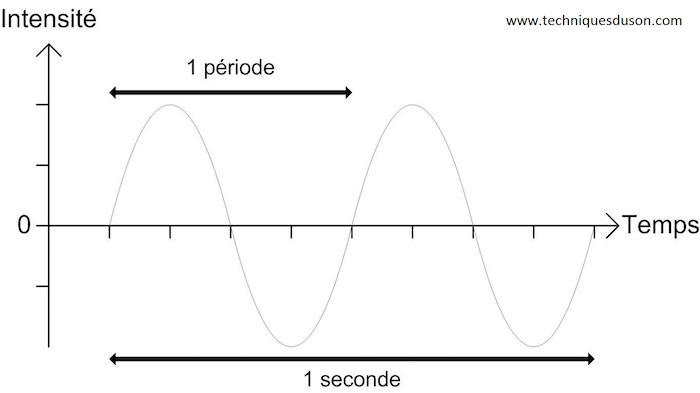

Here’s a diagram that shows you the principle:

Remember that the higher a sound, the higher its frequency will be. And conversely, the lower a sound, the lower its frequency will be.

Thus the frequency corresponding to a didgeridoo in D is 74.43Hz, which means that such an instrument makes the air vibrate 74.43 times per second. Do you understand? Great! So, let’s continue!

Here’s a table that groups the correspondence between notes and frequencies.

For information, the range of didgeridoos is located very, very (I could even add a third one!) predominantly in the space framed in red on the table.

Table source: http://colmard.com/Arduino-lecon7.html

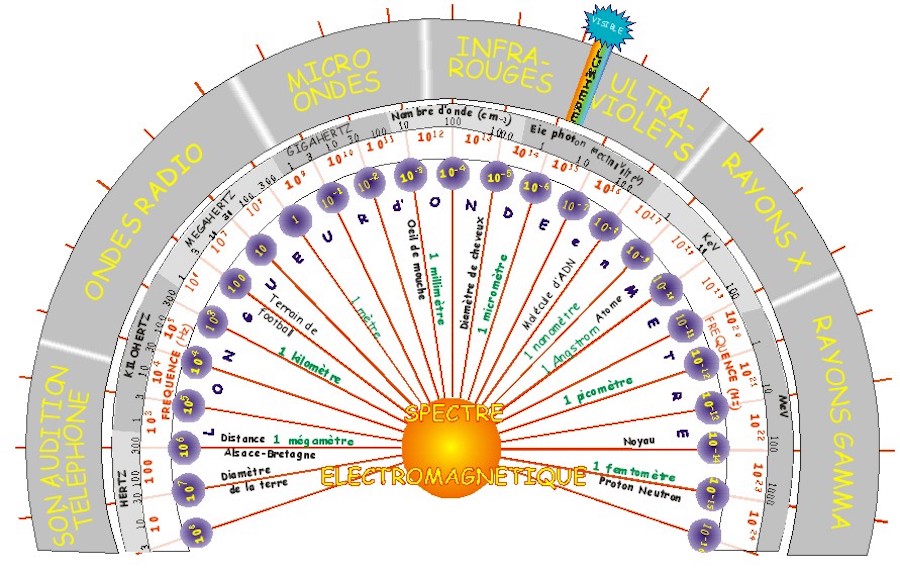

To make a small digression, where it starts to get interesting is that these frequencies don’t stop at just musical notes. We hear it quite often these days: everything is vibration. Thus, the sound world is only a tiny part of the frequencies that make up our universe. Here’s a diagram that shows that ultimately light, colors, radio waves, infrared are just frequencies that vibrate much faster or conversely much slower than sounds. Isn’t that crazy?! The first time I discovered this, it blew my mind. I said to myself: “But actually, when we make music, we’re painting, it’s sound painting. Amazing…!”

After that, you can do what you want with it… I found it quite amusing.

Source: http://catherine2205.free.fr/physique/spectre_electromag.html

The law of harmonics in music

After this poetic-metaphysical moment, let’s return to our beloved subject.

Let’s summarize what we now know. We’ve seen that each didgeridoo has its note and that each note corresponds to a precise frequency. Good!

Now, we’re going to complicate things a bit. You might suspect it, but it’s not just the fundamental that vibrates when you blow into the didgeridoo. Otherwise, we would just hear a linear sound that we couldn’t vary (or very little).

Thus there are other frequencies that overlap with the didgeridoo’s note. These frequencies are called harmonics and their combination gives the timbre of each instrument. Thanks to them, we can easily differentiate the sound produced by a singer from that produced by a trumpet, for example.

These harmonics don’t come randomly, they correspond to a series very well known to musicians, because we find it everywhere. To discover them, you just need to take the fundamental and multiply it by one, then two, then three… etc.

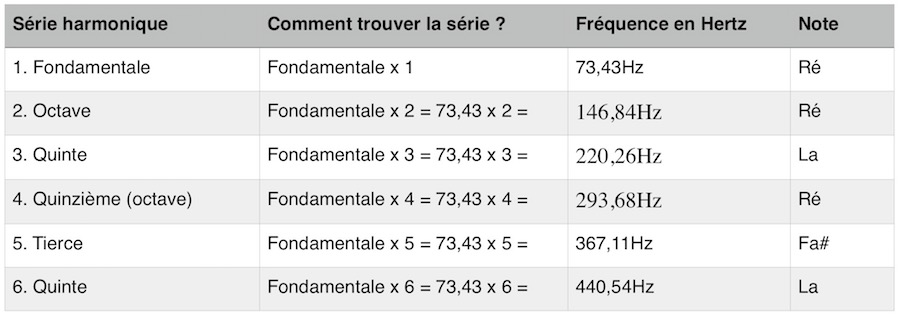

Here’s what it gives for a didgeridoo in D:

As we saw previously, a didgeridoo in D vibrates at 74.43Hz, this frequency represents the first harmonic, it is our starting point.

The second harmonic is at the octave, so it will be a D, but higher, vibrating at 146.84Hz. Then, we go up to the fifth then to the fifteenth…etc… Ouch, am I losing you?…

Well, it’s true that that’s a lot of information, especially if you’re discovering all these terms at once.

To tell the truth, the octave, the fifth and all that jazz, we don’t really care about it.

What’s important is to understand that there are a multitude of frequencies that are produced when you play your didgeridoo. And that these respect an order that will always be the same on each instrument. This order corresponding to a very simple law which is the fundamental multiplied by 1, 2, 3…

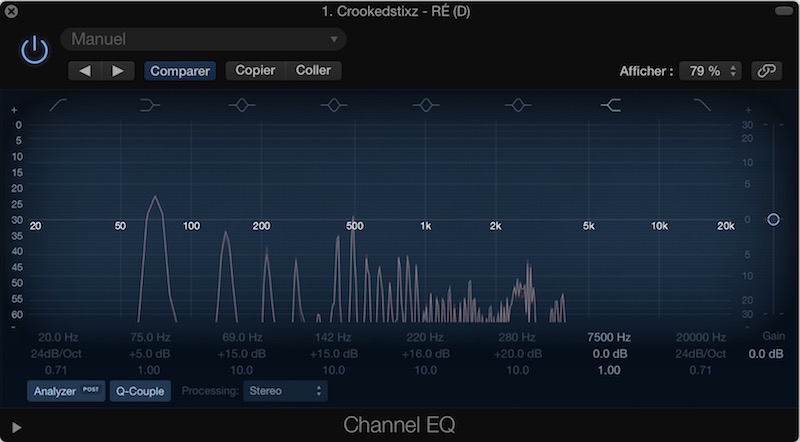

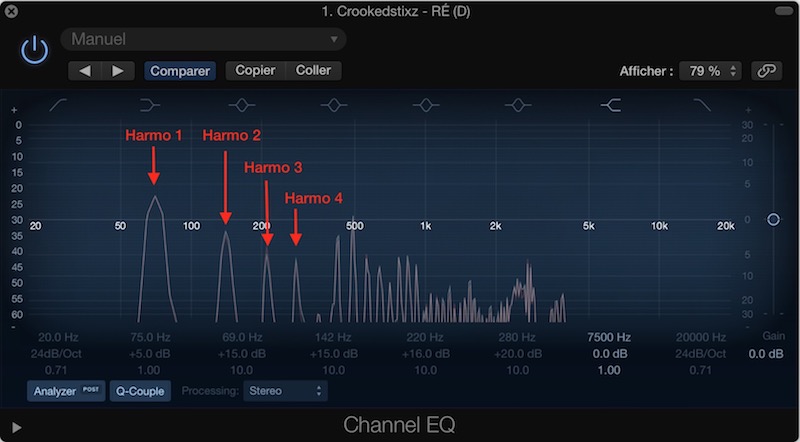

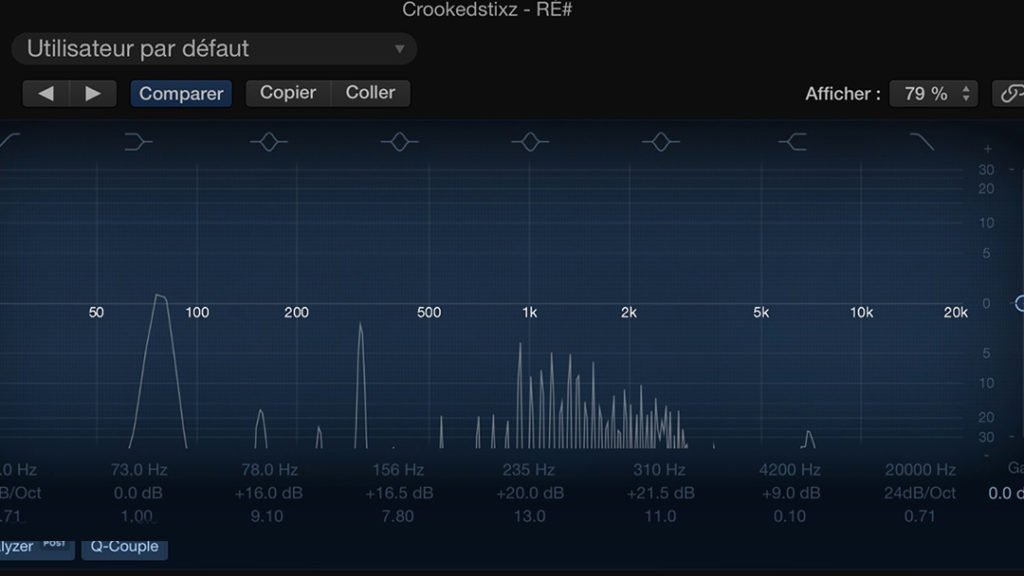

I suspected that this theory could be tedious. So I prepared something to stretch your brain. Here, for example, is what the frequency spectrum of a D didgeridoo from Crookedstixz looks like.

We can see very clearly, four first peaks starting from the left.

We just studied these first four harmonics. We have the fundamental, which I remind you, is the note of the didgeridoo (in D here) then the harmonics that follow.

Here’s the same diagram that shows you what these frequency peaks correspond to.

Harmonic 1 = about 73.42Hz = D, referring to the table above, we see that this is indeed the note of our didgeridoo.

Harmonic 2 = 73.42Hz x 2 = about 146.84Hz = octave = D

Harmonic 3 = 73.42Hz x 3 = about 220.26Hz = Fifth = A

Harmonic 4 = 73.42Hz x 4 = about 293.68Hz = Fourteenth = D

Beware of confusion around didgeridoo harmonics!

Harmonics are often subject to some confusion. In the didgeridoo what is commonly called harmonics, is nothing more than amplified vowels like: O, A, E, or I. In this case, the tongue will position itself in such a way that it will amplify a precise frequency of the didgeridoo corresponding to the articulated vowel. Generally, these frequencies are between 500Hz and 3500Hz.

In this article, when I talk about harmonics, these are those located in the lower frequencies. They are very close to the drone and often between 50Hz (first harmonic of a didgeridoo in A) and 500Hz.

The main difference with vowels and these “low” harmonics is that we have almost no action on the latter. They are part of the didgeridoo’s drone. That is to say that no matter what sounds we articulate with the tongue, these harmonics remain present.

To differentiate them, we could very well say that vowels are active harmonics, because they depend on our action. And that conversely, the drone harmonics are passive, because they are naturally present in the sound.

What follows is even more exciting (yes exciting, that’s a change isn’t it?). I recorded the sound of four didgeridoos to show you how the first harmonics of each instrument sound (I’m a bit tired of repeating didgeridoo all the time!).

In these recordings, I amplified the harmonics one after the other so that you can hear them well (I would have liked to do more, but the software limited me to four).

If you read my article on didgeridoo psychology, you know the two main shapes of a didgeridoo: conical and cylindrical.

For the exercise, I had fun comparing the frequencies of four instruments, classified by note and shape:

- Two didgeridoos in D: one conical (CrooKedStiXz) and the other cylindrical (Bob Druett)

- Two didgeridoos in C: the first is conical and made by Marcos Ferrazza and the second is cylindrical and comes from Alex-didg.

Let’s go for the sound, nothing beats theory in action!

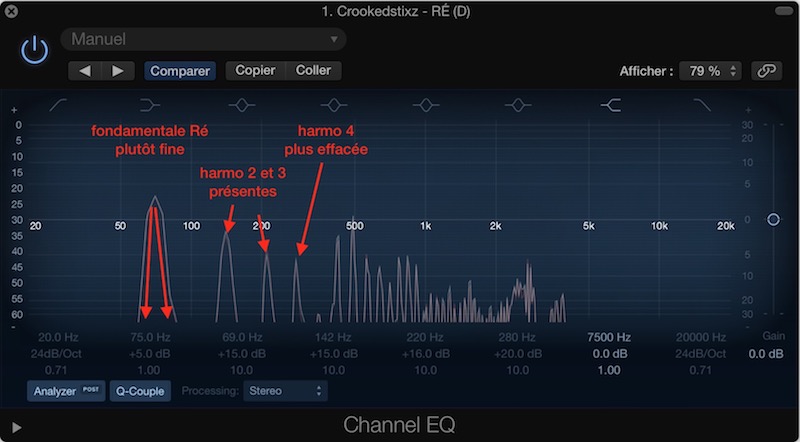

Conical didgeridoo in D made by CrooKedStiXz

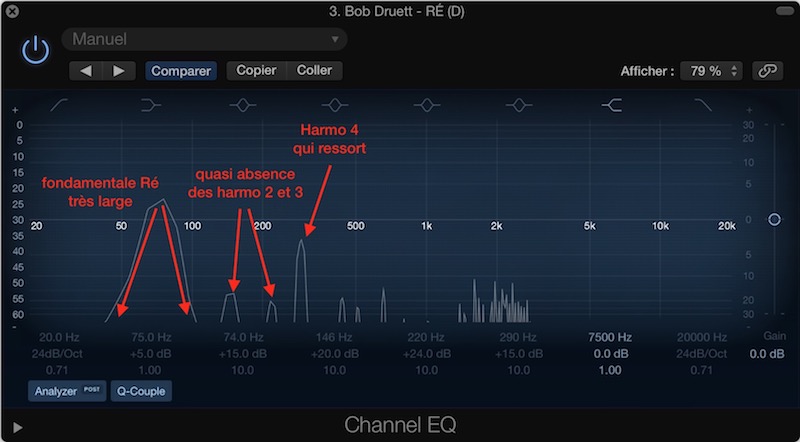

Cylindrical didgeridoo in D by Bob Druett.

Conical didgeridoo in C by Marcos Ferrazza.

Cylindrical didgeridoo in C from Alex-didgeridoo.

Thanks to Greg from didgeridoo-passion (also listen in French to: From the Nomadidge festival to Aboriginal Australian culture, meeting with Grégory Zwingelstein) for allowing me to record the didgeridoos from CrooKedStiXz and Marcos Ferrazza!

Effect of a didgeridoo’s shape on its sound spectrum

There, have you watched the videos? Do you understand better now what I explained above? Just remember that most of the time the first 5 frequencies define the character of a didgeridoo.

By the way, did you notice the main difference between conical and cylindrical didgeridoos?

The conical shape of the two tested didgeridoos amplifies the first four harmonics almost equally. This has the consequence of giving this cavernous and earthy effect. Nothing more normal: its first four harmonics connect it to the ground.

As for the two cylindrical didgeridoos, they only amplify the first harmonic (fundamental note) and the fourth, leaving harmonics 2 and 3 almost inaudible.

You may have also observed that the fundamental is much “thicker” in Bob Druett’s D than in CrooKedStiXz’s. When we know that Bob’s didgeridoo is much wider than the second, it’s quite amusing to see that we find this “anatomy” in the spectrum of the two instruments. However, this is not the case with Alex-didg’s C, this factor might be related to the weight of the didgeridoo.

Cylindrical didgeridoo in D by Bob Druett

Conical didgeridoo in D by CrooKedStiXz

Singing Didge: a didgeridoo that sings

Last December, I started working with Adam, Australian maker of CrooKedStiXz. By the way, he does really excellent work, I highly recommend him. So I received a D# didgeridoo that he had made according to my requests. From the first second I blew into it, I fell in love with this didgeridoo. Do you know why? Because it sings! Listen instead:

Do you hear that frequency that sounds well above the others? It’s (again!) this fourth harmonic that dominates the spectrum.

I amplified it on the same recording so you can hear it well.

Cylindrical didgeridoo in D# by Crookedstixz

Didgeridoo in D#

Fundamental: D# = 77.78Hz

Octave: D# = 155.56Hz

Fifth: A# = 233.34Hz

Fifteenth: D# = 311.12Hz

Third: G = 388.9Hz

Fifth: A# = 466.68Hz

To make sure we’re talking about the same thing, I specify that it’s the amplified harmonic that is the furthest right in the video, the one that vibrates at 310Hz. It offers a warm presence to the didgeridoo.

We’re dealing with the same pattern as Alex-didg’s C didgeridoo and Bob Druett’s D (both tested above). However, the fourth harmonic is particularly present in this D#.

I always say that such a didgeridoo is an instrument that sings, and believe me, they are very rare to find. Indeed, few people pay attention to this and therefore makers don’t necessarily focus their research in this direction. Most of the time, we seek power at the expense of these fine frequencies.

Conclusion: listen (again and always) to your didgeridoo!

My hope is that you educate your ear. Because it’s in my opinion, the only way to develop your playing. Once again, we don’t give a damn about the theory developed here. It’s not important for blowing into a piece of wood! When I started playing, I had absolutely no awareness of all this, and to tell you the truth, it annoyed me quite a bit!

I just wanted to blow. However, I quickly heard these didgeridoos that sang. Very often, other players didn’t understand why I loved this didgeridoo so much rather than another more powerful and easier to play. At the time, I couldn’t say the cause of my love for such a singing didgeridoo! I was content to say: “It has a presence in the sound that is super beautiful.”

I was far from scientific rigor and I completely ignored the presence of the fourth harmonic, but I heard it and that was the main thing.

So, stay tuned to your didgeridoo, stay vigilant, and never stop developing your listening! (To watch: Are you ready to listen to your didgeridoo?)

Comment, share, like… if you think this can bring a little happiness and understanding to other players!

35 Responses

Thanks Doris for your notes, I don’t have that knowledge for music theory.

bonjour

merci pour l’article génial

par expérience , pour moi , le didg (peut importe la forme ) chantera plus si la note du bourdon est accordé avec la note de ta voie chanté , et si tu envoi avec l’intention (c’est peut être pas le terme exact) la vibration au tier du tube : j’ai remarqué que par l’intention on pouvait varier le son suivant que tu plaçai ton attention dans ton crane , dans ta bouche et a divers point de l’instrument ( comme en chant diphonique , histoire de résonateur)

je suis actuellement en train de finir un nouveau didg en agave (donc conique) je remarque que l’embouchure ( la longueur de la réduction) joue aussi énormément sur la présence des harmonique intermédiaire.

des photo de mes créations : https://sites.google.com/site/pyvesweb/curiculum/creations-artistiques

merci pour ton travail sur ton site

Merci pour ton retour Jean-Yves. Je ne suis pas certain de voir exactement ce que tu veux dire mais dans tous les cas, c’est le genre d’échanges qui passent mieux de visu. 🙂

En tout cas, je te souhaite beaucoup de joie à souffler dans ton nouveau didge !

Merci à toi pour ce papier Gautier. Je le prend 2 ans après son écriture visiblement.

Mais là je viens d’apprendre un truc. Merci à toi

Punaise, tu as raison quasi deux ans déjà que j’ai écris cet article !

Il y aurait encore beaucoup à dire. La recherche est passionnante.

bonjour Gauthier, tout est vibration, nous mêmes sommes en vibrations et d’ailleurs nous concernant elles sont très basses si nous sommes assujettis au mental, par contre si tu arrives a élever ta vibration tu t’apercevras que tu n’est plus sous la dominance de la gravitation.

video a voir sur youtube de NASSIM HAREIM un physicien autodidacte qui a découvert la maitrise de la gravitation

ça revient a dire ce que tu exprimais dans ton livre sur le jeu intuitif, ce n’est plus toi qui joue mais la présence de ton jeu

il y a encore tellement a découvrir sur nous mêmes , nous sommes bien souvent envahi de toutes nos mémoires

Oui, c’est vrai que la physique nous dit que le monde est vibration. 🙂

Ce que j’aime encore plus avec la musique c’est que ces vibrations sont concrètes. On peut les sentir et jouer avec. C’est tout l’art du musicien je crois.

Yo! Ok merci.

Ta méthode est en vente en ligne?

Je suis justement en train de mettre tout en place. Elle sera en vente via mon site dans les prochains jours. 🙂

Super intéressant!

Quel logiciel et quel micro utilises-tu?

Où et comment obtenir un Didge qui chante?

J’ai encore du mal à m’y retrouver dans les notes et les gammes pour choisir un Didge dans le sens où tu dis que ça commence au La je crois, alors que pour moi c’est Do le plus grave….

Merci

Salut Niko,

Désolé pour mon temps de réponse, Le Rêve de l’aborigène était le week-end dernier… J’ai utilisé Logic Pro pour faire le test.

Pour obtenir un didg qui “chante”, là il n’y a pas de secret, il faut en essayer encore et encore et développer son oreille. Pas de recette miracle pour ça… 🙂

Le Do est le plus grave si on commence la gamme en Do mais tout comme le piano a encore des notes après un Do au centre de celui-ci, le didg a des note plus grave que le Do. J’espère t’éclairé ! …

Merci Gauthier.

En effet sur le thème du “chant” du didgeridoo, il y a des idées à creuser. Continue de nous faire part de tes avancées.

Manu

Salut Gauthier

Je trouve cet article très intéressant. J´ai une remarque et deux questions.

Je ne comprends par la phrase : “Rien de plus normal : ses quatre premières harmoniques le rattache au sol”. Peux tu élaborer ?

En passant, il y a accord pour le verbe : “le rattachent” 🙂

La première question porte sur les didgeridoos qui chantent (soir et matin). Est ce que la voix peut favoriser l´amplification de cette 4ième harmonique. Quand je joue, certains jours, j´ai l´impression que le didg “chante”. Peut-être que ces jours là, j´ai juste une oreille plus attentive ou que quelque chose dans la pièce amplifie une fréquence.

Le deuxième question porte sur d´autres harmoniques qui pourraient faire “chanter” le didg. Est ce le cas ?

Bonne journée et encore merci pour cette analyse.

Manu

Salut Manu,

Merci pour la coquille, elle est corrigée. 🙂

Pour la phrase : “Rien de plus normal : ses quatre premières harmoniques le rattache au sol”, je voulais dire par là qu’un didgeridoo conique à ses quatre première harmoniques très présentes. Celle-ci, comme on l’a vu se trouvent dans les basses fréquences et les bas médium. Elles renforcent donc les basses du bourdon. Dans ma tête, les basses sont rattachées à la terre, tandis les harmoniques et toutes les hautes fréquences ont le côté aérien du ciel. Ainsi, le fait d’avoir ces quatre harmoniques renforcent le côté “terre” du didgeridoo et donc le “rattache au sol”.

Est ce que la voix peut favoriser l´amplification de cette 4ième harmonique.

Je n’en suis pas certains mais je pense que oui. J’ai pu aussi remarquer que la voix aidait à faire ressortir certaines harmoniques du bourdon, en revanche je ne sais pas lesquelles et si celles-ci sont modifiées en fonction de la tonalité de la voix et de l’ouverture de gorge. De nouvelles recherches en perspective…

Peut-être que ces jours là, j´ai juste une oreille plus attentive ou que quelque chose dans la pièce amplifie une fréquence.

Soit ton oreille, soit la position de tes lèvres, soit l’ouverture de gorge, soit comme on vient de le voir la voix… Il peut y avoir pas mal de raisons à ça. 🙂

La deuxième question porte sur d´autres harmoniques qui pourraient faire “chanter” le didg. Est ce le cas ?

Je ne sais pas ! Je dirais que oui mais c’est encore à vérifier suivant les didgeridoos. Je pense cependant que ce sont très souvent la 3 ieme ou la 4 ieme qui chantent car elles font parti des basses fréquences du bourdon (harmoniques passives) mais sans être trop proche de la note du didgeridoo.

J’espère t’avoir éclairé !

Merci pour cet excellent article ! As-tu remarqué si certains bois généraient plus ou moins d’harmoniques ?

Quel logiciel utilises-tu pour faire les analyses ? Tu connais l’équivalent pour PC ?

Pour les bois, je n’ai pas poussé la question si loin. Il faudrait des didgeridoos à la configuration identique dans des bois différents, ce que je n’ai pas sous la main. Ça serait plus à un fabricant de didgeridoo de faire cette chouette expérience (quelqu’un est motivé ? :)). Ceci-dit en allant voir divers luthiers ou facteurs d’instruments, on a peut-être des chances de trouver des pistes.

Pour le logiciel, j’utilise Logic Pro, dans l’EQ de base, il y a une fonction pour afficher le spectre des fréquences. Je pense qu’en tapant sur Google : logiciel spectre fréquence tu devrais trouver…

Hello Gauthier,

super création ton article, je ne te connaissais pas ce coté scientifique!

Bien plus appétissant que le ” traité des objets musicaux” de Schaeffer!

Bon, je reprends mon bâton de pèlerin, afin qu’il me souffle quelques bizharmoniques.

a bientôt;-)

Salut Pascal,

Et oui un peu de science ne fait pas de mal !

Finalement, la science pourrait se résumer à l’observation des phénomènes afin d’en tirer des hypothèses puis vérifier par l’expérience celles-ci. Ce qui revient à faire ce que nous faisons durant cours, à savoir observer les mouvements de notre langue, lèvres, joues, mâchoire…

Je vais aller voir ce traité des objets musicaux mais rien que le nom me fait peur ! 🙂

Hello l’artiste ! 🙂 bien sympa et bien banalisé ton article, félicitation.

C’est intéressant de voir comme chaque musicien est sensible différemment aux fréquences, avec l’exemple des didg “chantant” que tu aimes bien. Car personnellement, a chaque fois que j’enregistre des didgeridoo qui ont des harmonique 3 ou 4 bien présente, je les baisse à l’équalisation, je n’aime pas comme ça tinte le son en fait 🙂

A bientôt !

Ah oui ça c’est rigolo, purée c’ets fou, comment ne peut-on pas aimer cette si belle fréquence. 🙂

On pourra s’organiser un échange de didg : je te file les miens qui “ne chantent pas” et tu me refiles les tiens qui “chantent”. 😉

Gauthier ton article éveille notre attention, nos oreilles seront plus attentives dorénavant.

Ma fille est bercée par ta musique, tous les matins elle me demande d’écouter ‘Larme de vie’, puis chargé d’ondes positives nous pouvons commencer notre journée.

Cela me fait très plaisir à chaque fois que l’on me dit que ma musique plait aux enfants. C’est un des plus beau compliment que je puisse recevoir, les enfants ont une tel innocence animé de spontanéité. On est sûr que ça vient du cœur !

Vivent les matins en musique. 🙂

Vraiment intéressant et passionnant même pour les débutants, surtout s’ils sont curieux.( sur les leçons de ton disque les harmoniques sont trop belles et je rame, je rame …) Bravo et merci yves

Merci Yves !

C’est vrai que la précision des harmoniques demandent beaucoup de boulot, et c’est un travail qui ne termine jamais… Patience et persévérance sont de mises !

Merci Gaultier pour cette article passionnant! Ca me donne envie de preter plus l ‘oreille sur les harmoniques du didg dorenavant et sur tout autre son d ‘ailleurs 🙂 Ca m a fait penser à un documentaire sur la resonance et la création que je t ‘invite à visionner si ce n est pas deja fait! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a_kVTStbSuY .

ET bonne année!

Merci Adèle pour le lien et meilleurs vœux à mon tour. 🙂

Je vais aller voir ce documentaire !

HAaaa! ce Gauthier ! Repoussant toujours au plus loin la connaissance de ces jolis tubes 😉

super article. Merci pour tout ça et pour tout ce qui suivra 🙂

bonne année

Merci Hadrien 🙂

Je suis très content de voir l’engouement que cet article suscite. J’y ai passé du temps mais ça m’encourage à continuer dans ce sens ! 🙂

Et bonne année à toi aussi !

Superbe article, du gros boulot ! Bravo

Merci :). C’est aussi grâce à toi tout ce travail !

J’avoue que tout le tralala sur la physique me dépasse, mais je comprend ce que tu veux dire pour l’avoir expérimenté sans vraiment m’en rendre compte sur les miens. Je te remercie pour tout le travail que tu partages. Om

Je comprends que la physique puisse est barbante (et encore là on reste en surface !) mais si elle peut aider à mettre des mots sur ton ressenti alors, à mon sens, elle aura remplie son rôle ! 🙂

Excellent article très intéressant. Petite remarque dans la comparaison conique cylindrique. N’as-tu pas fait une erreur ? Tu parles à deux reprises des cylindriques., quid des coniques ? Une coquille je pense 🙂

Merci Marc, c’était bien une coquille. Elle est corrigée. 🙂